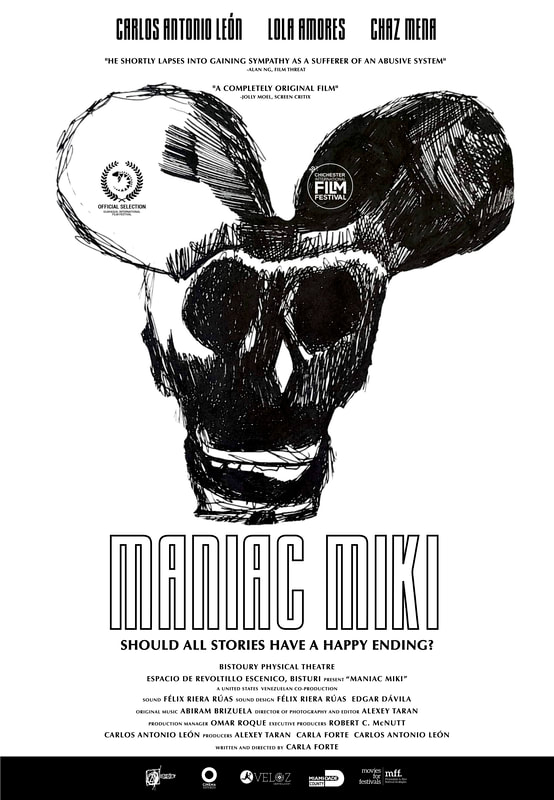

by TRAE DELELLIS, Miami New TimesMiami can seem like a bright place, but in reality, it can be downright dark. For proof, you only need to see filmmaker Carla Forte's Miki Maníaco. It is a tale of celebrity, exile, and malcontent. Miki Maníaco follows its titular character, Miki, a former children's entertainer in professional ruin following his banishment from the industry. Literally washed up, Miki lives on a tiny boat with his former professional partner and lover, Mimi. The film alternates between the couple airing their grievances adrift in the water and an E! True Hollywood Story-esque documentary project about Miki and his former fame. The film opens at O Cinema South Beach tonight, September 2. A darker-than-dark comedy with surreal and satirical flourishes, Miki Maníaco isn't a film for everyone, but nor is it worried about pleasing everyone. The first images in stark black-and-white contrast the conventional imagery of Miami, one of sun, greenery, and neon nights. The South Florida setting was integral to Forte's vision. Having moved from Venezuela in 2007, Forte was interested in Florida as a "state that has always been known as a place of transition and retirement for the country." Both accurately describe Miki's predicament. He is treading water, trapped in a moment of transition brought on by his forced retirement from the entertainment industry. A former performer with a slight messiah complex, he's in purgatory, awaiting salvation or damnation. Amid the angry diatribes of a "forgotten man" and existential questions from a disembodied documentarian Forte intersperses sublime scenes of striking motion such as dance, a man seemingly walking on water, and a triumphant pack of dogs. They perfectly contrast the dark humor and bitter tone of Miki Maníaco, which is ultimately a film about how systems (or industries) can discard and dehumanize people and potentially create monsters. Central to Forte's film is a deconstruction and interrogation of the "Dream Americano" and experience of exile, rooted in her experiences as a Latin American artist living in the United States. "In Latin America, we perceive the American Dream in a very particular way," Forte explains. "We think of it as a delusion, [one that] we can only really understand once we live in the United States." In many ways, the film is a satire about bureaucracy and cruelty with shades of Kafka and Buñuel. Again, these overarching ideas emerged from Forte's own experience. Fueled by frustration with the constant consumption of the entertainment industry, Miki Maníaco is a therapeutic and cathartic product of confronting those ideas. Forte's exploration of deteriorating fantasy is one of the film's most fascinating elements. It can be seen in Miki Maníaco's subversion of Disney tropes. Each of the characters' names is derived from a classic Disney character: Miki, Mini, Donalt, and even a brief cameo from an Ariel-like figure, as Forte takes abstract aim at the illusions and delusions we're fed by the entertainment industry. As a child, Disney represented an ideal world to Forte, who, as an adult, is more interested in the fragility of fantasy. Firmly believing that the perfect place does not exist, she remains fascinated by the fractures of fantasy, extending to the country we live in, which isn't as solid as we thought it was. What interests Forte is how unhappiness can masquerade as happiness. Miki Maníaco is a dark film, for sure — a kind of Miami Inland Empire — but it is also fascinating and singular. This is partly due to the close collaborations between Forte and her cast and crew. The making of Miki Maníaco seems to counter its own dark tale of the entertainment industry and show the possibilities of local artists working together to create art. Working closely with Forte on the project is cinematographer and editor Alexey Taran. In 2005, Forte and Taran founded Bistoury Physical Theater and Film, a platform for avant-garde dance, theater, and film. The translation of avant-garde theater, mainly regarding movement, provides an intriguing component to the film. Forte values the partnership, saying they speak the same language. An interesting addition to the creative team is first-time collaborator Abiram Brizuela, who contributed a musical score that provides some of Miki's haunting moments. The final piece of the puzzle is the actors, Carlos Antonio León (Miki), Lola Amores (Mimi), Chaz Mena (Donalt), and Jose Manuel Dominguez (Mailmain), who give equally frenetic and committed performances. Conveying such disgruntled and aggrieved characters requires trust between director and actor. Forte, who worked closely with each performer, says it was all about unmaking the characters — and that they had a lot of fun doing it. Supported by O Cinema, this project is quintessentially made in Miami and is an example of what independent film can do in the city. In its entirety, Miki Maníaco is like a funhouse mirror. The image can be distorted and grotesque, yet you can't look away. Forte and her collaborators have crafted an allegorical tale about the warping of the American Dream, fully aware that it has always been warped. Miki Maníaco. Friday, September 2, through Thursday, September 8, at O Cinema South Beach, 1130 Washington Ave., Miami Beach; 786-471-3269; o-cinema.org. Tickets cost $11. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorBistoury Physical Theatre and Film Archives

March 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed